Interview with Don Taylor, Bookbinder

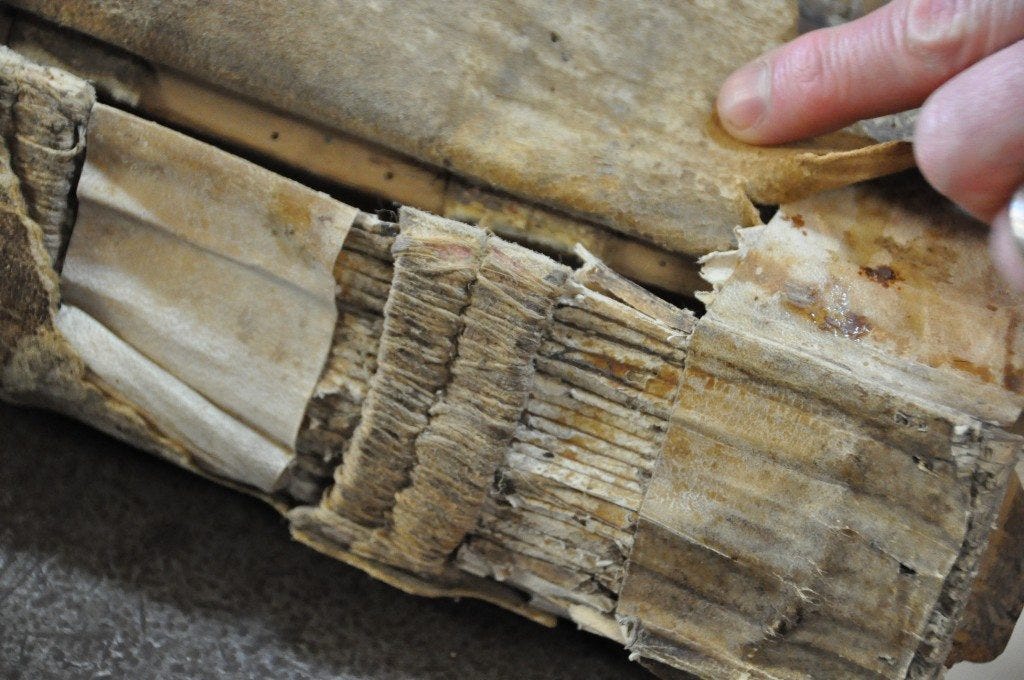

I had the pleasure of interviewing Don Taylor recently, a bookbinder based in Toronto. Don's been in the industry for thirty years, his work ranging from personal publications under Pointyhead Press, collaborations with colleagues, design book bindings, and, of course, book restorations. So without further ado, here he is! Let's start with something easy! What's the oldest thing you've restored? Well, for several years I worked on a collection of medieval manuscripts, mostly brought to me for rebinding. It was for a very rich and eccentric guy; he wanted all the books to have red leather bindings, and he mostly got his way, even though I tried to talk him out of it. He wanted the bindings replaced rather than restored. Wrong, in my opinion, but if the whole job depends on that, I'm going to do it because I want to experience the books. In turn, I tried not to disturb the sewing too much. Lasted about 15 years. ...How many? Fifteen. He had about 150 of them. I didn't go in every day, of course. I'd go in a couple times a week in the morning so it stretched out. So he had the bindings replaced instead of restored. What are your thoughts on people just casting aside their old bindings? I don't like it, I think the originals should be kept as much as possible, but sometimes you just can't convince them to do that. I keep some of the more interesting pieces. With this one, for example, it's from 1506, and you can see how all the pages were cut out and sold. It was an antiphonal: choir music. All the structure is still there: the little straps of alum-tawed pigskin, the parchment liners, the sewing structure in a figure 8 pattern, half-inch thick boards. And, of course, the brass studs. [twocol_one]

[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

[/twocol_one_last] [twocol_one]

[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

[/twocol_one_last] What were the studs for? They're called bosses, and they're there to protect the surface of the cover. Normally the book would've been open on a lectern and the bosses would prevent the leather from wearing. A German professor of mine called them biernägeln: beer nails. He and his friends used to joke that the studs were there so that if you spilled beer on the table, it'd flow under the book. But anyways, the point is that we try to salvage old bindings as much as possible. Kate Murdoch, the woman I work with, does a lot of this kind of thing. Here she's repaired the leather. Doesn't look like much was done, but it's back to being neat and functional. [twocol_one]

[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

[/twocol_one_last] The point is to keep intact the cloth, leather and original material as much as possible, have it look as authentic as possible, and make it functional again. Here, let me show you this beauty. [twocol_one]

[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

[/twocol_one_last] [twocol_one]

[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

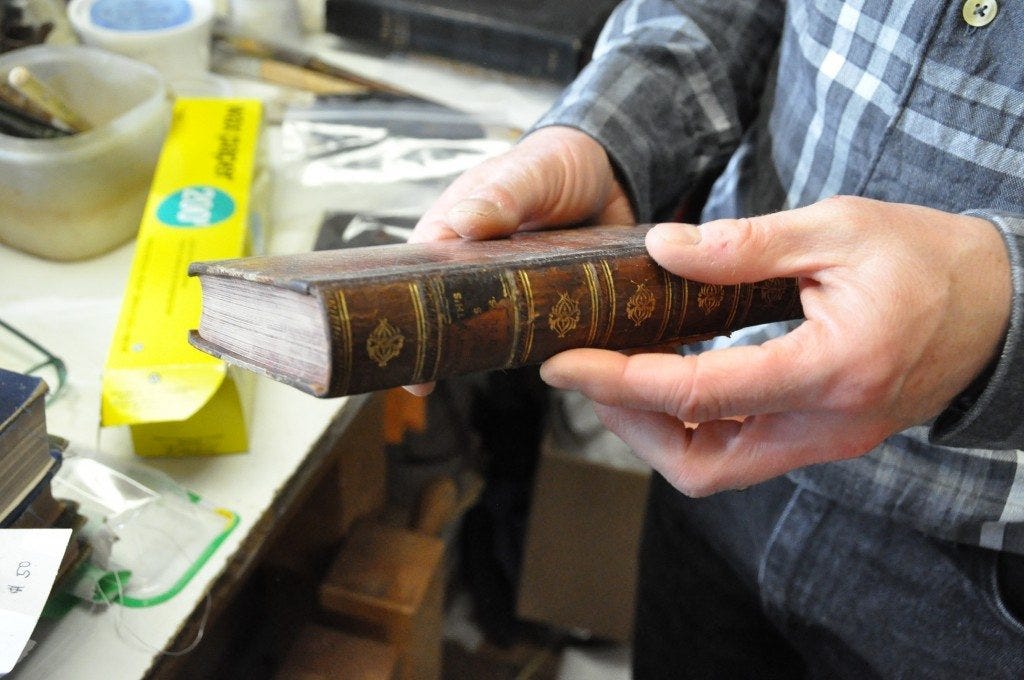

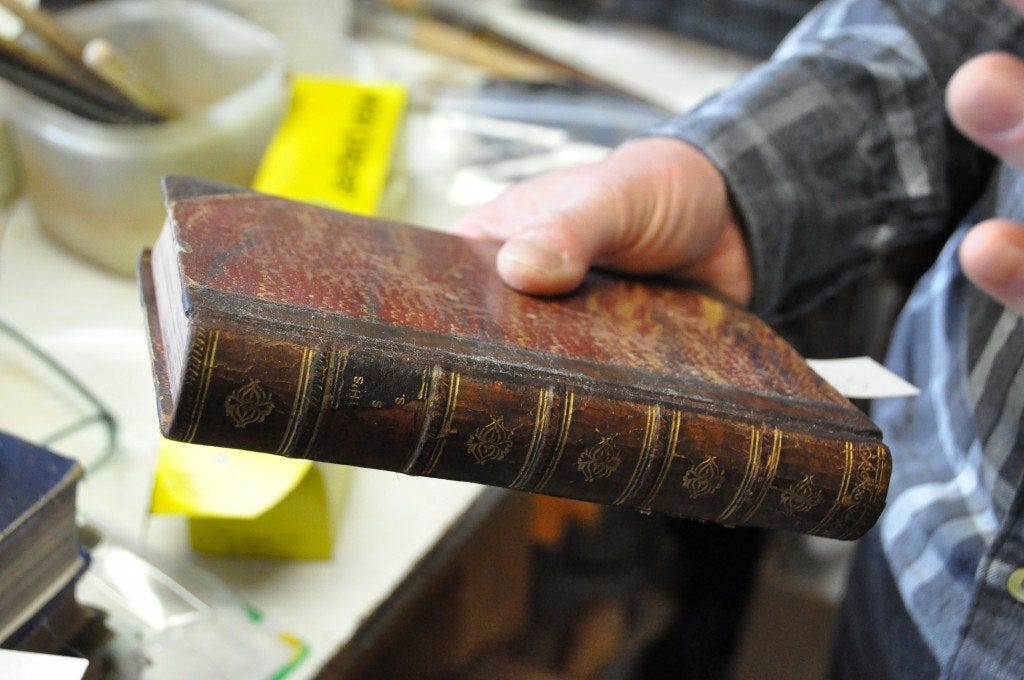

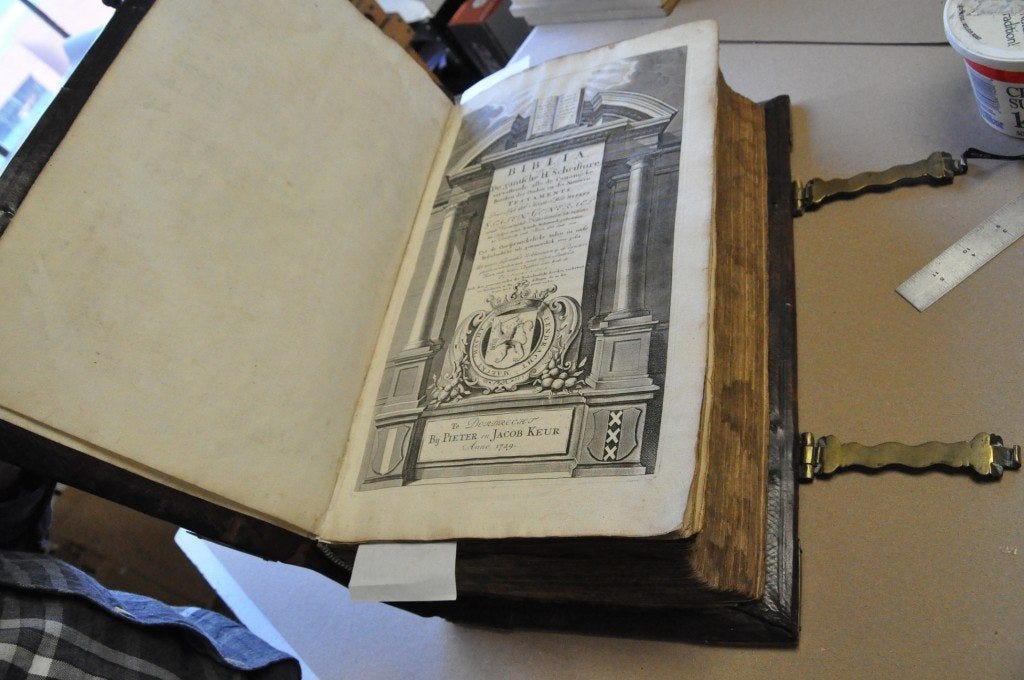

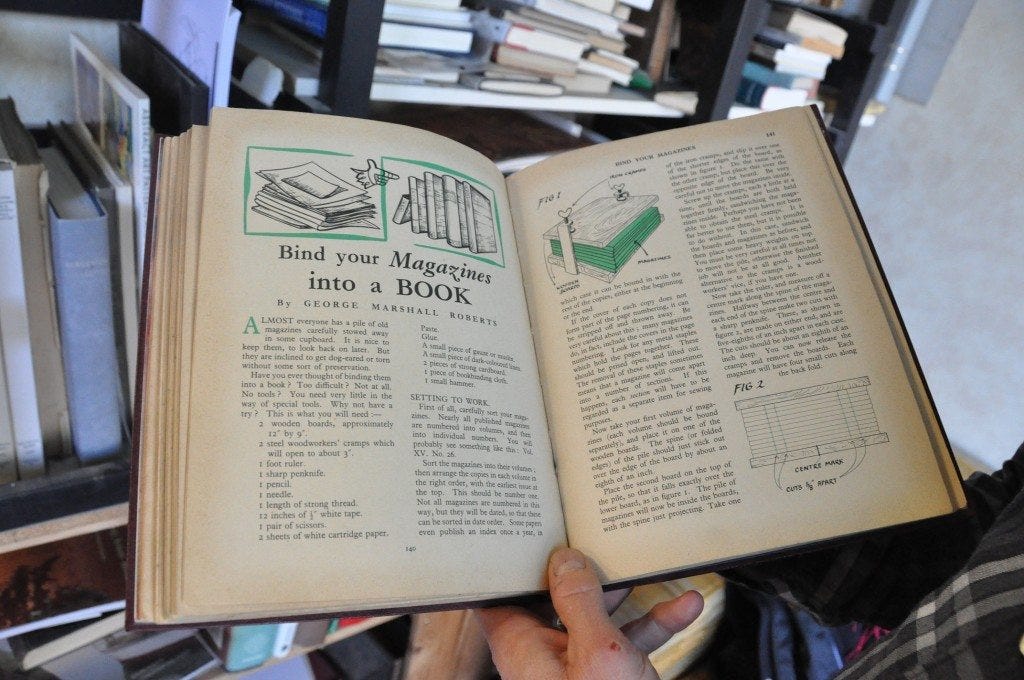

[/twocol_one_last] This is an 18th century bible, and those are handmade clasps, not stamped out of sheet-metal. It was water-damaged and needed a new spine. You can see where the old leather meets the new. All the hardware had to come off—the boards of wood, the clasps. The fun part was that one of the clasps had broken and we aren't metal-smiths, but we know a few, so we had one of our buddies re-solder it. That's stunning. I always wished I had these kinds of things in my family. Geez, nobody has this stuff, come on. Only rich eccentric millionaires. Exactly. But yeah, we see everything. Old things like that, not too much medieval stuff after the 15 year job, but some really exotic stuff. There was a Koran that was about 150 years old that was very badly damaged but beautiful, all hand-written, and Kate did a great job restoring it. We also get to make props for movies and all sorts of fun stuff. That's fascinating. How'd you get into bookbinding? I've been in the business for 31 years. It was a hobby. As kids, my friend and I were really bookish, and we'd get books from Goodwill stores and tear them apart just to see how they were made. His father was an industrial arts teacher in high school and had a book on school projects: "How to bind a book" and "How to make a book press." Things like that. So I got interested through my friend, but preceding that was my grandmother. She sent me the Daily Mail Boy's Annual 1959, and in here is a section on binding magazines into a book. So a few years after I get it, I'm sick at Christmas, and I take a bunch of my MAD magazines and sew up my first book. The instructions are pretty weird, so it looked really strange, but that's how I got started.

My friend eventually became a musician, but I grew up in Windsor, wanted to leave, heard about a book-binding night course in a high school in Toronto and thought hell, maybe I should move there! So on the strength of that... Yeah I was pretty bored in Windsor. There were also courses on bookbinding in England, but of course they cost the earth, so I just hung out here in Toronto. Lessons through the high school at night— Do those still exist? No, there's nobody to teach them. Or at least no money to pay anybody to teach them. There might be something out there, but this guy was the real deal. Properly trained, doing it for a lark in the evening. We'd go out for beers afterwards. When he gave it up, nobody stepped in. Anyways, I did that for a bit, and then by a miracle, one of the deans at Sheridan College in Oakville got really excited about bookbinding. For some reason. I have no idea why! So he set up a hand bookbinding course as part of the art fundamentals, and there you have it! I decided to enroll, quit my job— What were you working as? Haha well...The reason I'd left Windsor was because I was a clerk at the Canada Pension Plan. Could've been retired by now with a nice government pension! But it was the kind of job that sucked the life out of me, so I moved to Toronto and worked in bookstores and the like. When you've already quit a steady government job in favour of a job at a book shop, quitting again in favour of college isn't too big of a deal. I had some money saved up so I financed myself that way and just went with it. It sounds like a really small community. Is it getting smaller? Is there lack of interest? No, there are always people like yourself that are interested and take courses, and I even do some teaching from time to time. The Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild has been going for a good thirty years now, and they do exhibitions and things. The community is small, but it's spread out. There are people all over Canada, but maybe just one in Saskatchewan. The Guild started in Toronto but now there are chapters in Calgary, Ottawa, Vancouver, Victoria, some stuff going on in Halifax, and that's actually a growth. So to answer your question, I don't think it's shrinking.

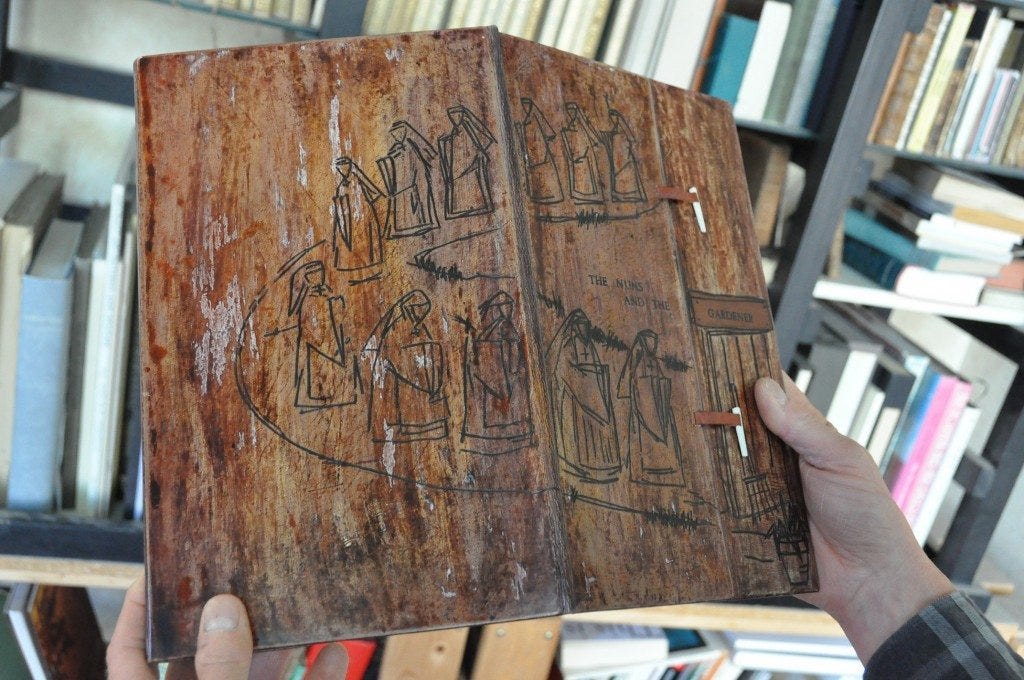

The Nuns and the Gardener from Boccaccio’s Decameron. Tooled leather and bone catches. Made for a CBBAG exhibition.

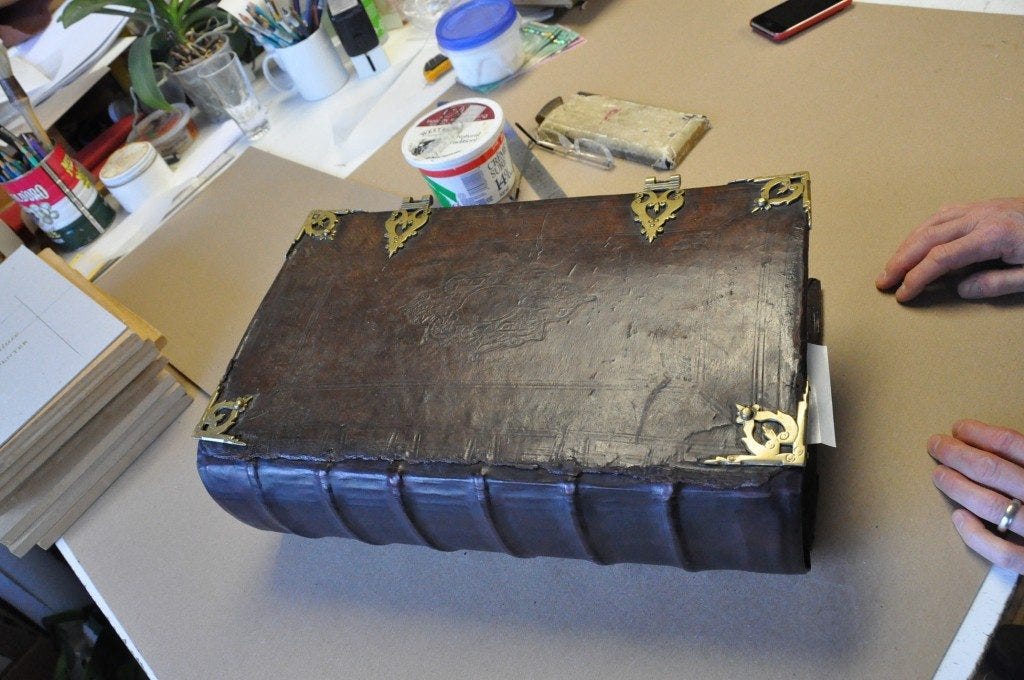

That's good to hear. There are some things I can think of that leave me disheartened about the future of bookbinding. E-books, for example. Well I think the more you hear about e-books the more it just means that there's interest. I think a hundredth of people that are interested in e-books are going to be interested in letter-press printing as well. There's that same kind of small group of people that are always going to want to do this kind of thing. I think e-books are okay. I'm not remotely interested in them, I don't think they're evil or good, I just think they're something else. I don't regard them as the future of the book; I don't regard them as the death of the book. It's just something else. Another part of the book. Exactly. Back to restoration. What's the coolest thing you've restored? There was a 14th century manuscript a few years ago that had been wrapped in newspaper and buried in the ground for years. It was buried during WWII to prevent the Nazis from getting it, and then left in the ground to prevent the Communists from getting it. It was the kind of time period when everybody was stealing everything. It was eventually unearthed, but in terrible condition. I've still got the boards and spine here. [twocol_one]

[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

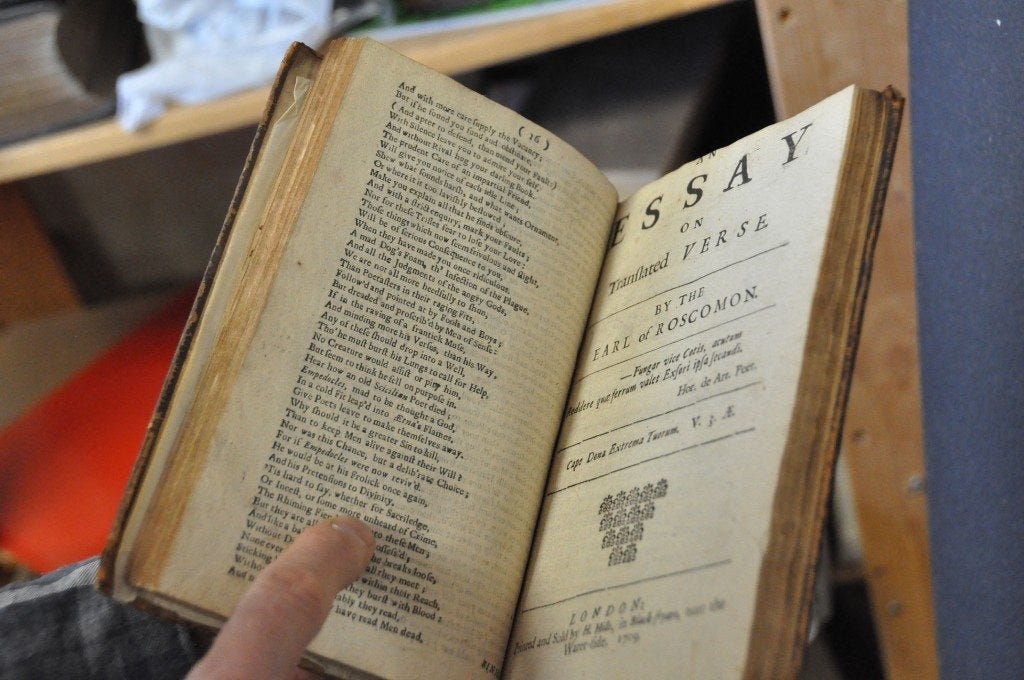

[/twocol_one_last] You can tell in the spine that the binding was later than the manuscript; it's in the tooling. Also, they never would've called it a Manuscript [MS] in the title. And you can see the wooden boards how they just split right in half. Totally water-damaged. I spent probably six months just stretching out the vellum. Vellum, being calf skin, is very susceptible to moisture, and both loses and absorbs it really easily. Being in the ground all those years really screwed up the vellum; made it totally wrinkled and distorted. A lot of the work was just stretching it out and trying to bring it back to its proper flattened shape. That was probably the most intensive thing I've ever done. One last question. Do you have a favourite time period? I think the nicest books that I've ever worked on myself have been that 18th century period. This example is sadly overtrimmed in the pages, but just the aesthetics of the period, the typeface, the slight roughness, the touch of craziness, I think it's beautiful. [twocol_one]

[/twocol_one] [twocol_one_last]

[/twocol_one_last] In terms of bookbinding, as opposed to printing, I really like the early 20th century French bindings. This was a sort of golden age of design book bindings. Schmied and Paul Bonet were some big names back then, and the crafting and tooling was really, really nice. I love this kind of thing.

Alphonse Daudet's Aventures prodigieuses de Tartarin de Tarascon, Binding by Paul Bonet

via themorgan.org And who wouldn't? Thanks for the brilliant interview, Don! [hr]

DON TAYLOR is very active in the bookbinding scene, so if you're in the Toronto area and have some old family books that need a careful rebinding, he and his colleagues are a good bet. If you have any questions, leave them in the comments and we'll try to answer them! Until then, happy reading, enjoy that book smell, and be wary of cracked spines!